THE CHANGING FACES OF MONEY

5-minute read

By Shailen Bhandare

Curator of the Ashmolean's major exhibition Money Talks: Art, Society and Power

In this article Shailen Bhandare, curator of our Money Talks exhibition, tells us more about how the images of people and the symbols of power, despite the changes of history, have consistently been the face of the money in our pockets.

The Money Talks exhibition at the Ashmolean explores the place of money in our world through art. Works on show range from coins featuring Roman emperors, Hindu goddesses and abdicating kings, to banknote designs showing the most reproduced monarchs and controversial figures in history.

People, portraits and profiles

Money is instantly recognisable. It always has something to show. The images on the front and back of coins and banknotes need to signify their value, as money is a medium of exchange, but they also need to be trusted and validated.

A common form of such validation is portraiture. Human bodies, busts or faces on coins have been a tradition since the invention of coinage.

In Ancient Greece and Rome, coins were often considered as works of art and ‘monuments’, commonly depicting iconic leaders, events they were associated with and the gods they worshipped.

Silver coin of Ptolemy I of Egypt (323–282BCE) with head of Alexander the Great struck at Alexandria © Ashmolean Museum

In the Middle Ages, the Christian faith was often articulated into motifs that authorised coins. In the Renaissance, classical forms were rediscovered laying the foundations for realistic portraiture.

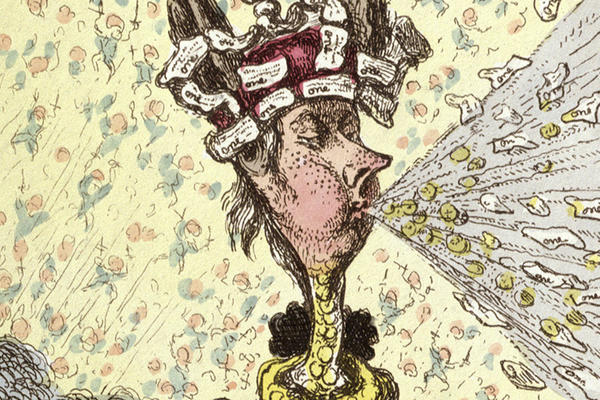

In Eastern cultures, gods and goddesses associated with prosperity and plenitude were often depicted on coins.

Gold dinara of Chandra Gupta II (AD375-415) showing Lakshmi, goddess of plenty, seated on a lion and making a gesture of scattering coins

By far the most common occurrence as far as faces on money are concerned, are royal portraits. One would wonder, 'why do we see these faces almost invariably as profiles?'.

The answer lies in the technology of coin production. Dies, or the tools used to strike coins, need to take heavy pressure while coins are being struck. The deeper the engraving, the lesser is the ability of the die to withstand the pressure.

Coin die to strike a £5 gold coin of George V

Profiles require shallower relief in engraving and in a profile view, one can often identify who’s being depicted from the silhouette alone. Profiles are therefore preferred over frontal portraits on coins. The choice between profiles and frontal portraits underscores how uniquely ‘money art’ is linked with functional aspects of money and its production.

Monarchs and Masters

Portraiture often comes with conventions – since the reign of Charles II, British monarchs have faced alternatingly on their coin profiles.

Profiles of British monarchs depicted on coins with Queen Victoria, Edward VII and George V facing in different directions © Ashmolean Museum

Edward VIII’s insistence to break this convention was grudgingly acknowledged by his government. Edward also wanted to move away from the traditionality of coin design.

Left: early design proposal for Edward VIII by Percy Metcalfe with king facing right, according to the convention, 1936. Right: finalised design by Humphrey Paget with king facing left against the convention, 1937 © Royal Mint Museum

Charmed by sculptor Percy Metcalfe’s use of animals on the ‘Barnyard Collection’ of Irish coins, he steered the artists designing his coins into creating ‘modern’ designs.

The final choice was a compromise between convention and innovation, but it gave the UK one of its most endearing coins – the ‘wren’ farthing designed by Wilson Parker. See our earlier article on the art of money to find out more about these barnyard designs.

Edward VIII bronze farthing pattern with wren design, Wilson Parker, 1937 © Royal Mint Museum

Edward VIII famously abdicated just before his coins were about to enter production and they were never issued. However, some reverse designs were used for coins of his successor George VI.

In the Money Talks exhibition you will also see, before you leave the gallery, the design for our current monarch's coinage. Martin Jennings' sculpture for the King’s head was commissioned by the Royal Mint.

King Charles III coinage model, Martin Jennings, 2023, plastiline on wood. Collection of the artist

Much as artists inspire money and leave a mark with their art, money too is known to have inspired artists. An excellent example is Peter Paul Rubens’ paintings of busts of Roman emperors. Rubens, a Master with an avid interest in studying and collecting Classical Art, made studies of profile heads of Roman emperors that appeared on their coins. He undoubtedly had access to such material through his connections with the Italian aristocracy.

Roman gold coin showing the Emperor Vespasian in profile, 510 BCE – CE 491 © Ashmolean Museum

Head of Vespasian, drawing by Peter Paul Rubens, 1600–8, after a coin, in pen and brown ink © The Trustees of the British

The Emperor Vespasian, Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) © Bridgeman Images

Rubens made paintings of 12 busts, converting the stylisation of coin portraits into an imagined realism to bring these historic figures to life. These paintings likely hung in a room full of antiquities in his house where Rubens showed off his Classical and Antiquarian interests.

Banknote intricacies and the Queen's devilish hair

Visual imagery on banknotes also charts a fascinating artistic journey. The primary concern about paper money is security – banknote design needs to ensure that they are not copied and forged.

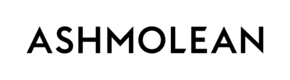

A host of technological innovations, like watermarks, ‘hidden’ features and holographic prints, are incorporated in a banknote to achieve this; however, the most popular way is to use intricate features of the depictions to enhance security. Subjects with curly hair, big bushy beards and moustaches are often preferred. But sometimes, these can backfire in strange ways.

Canadian bank notes display in Money Talks showing the young Queen Elizabeth's image

When artist-engraver George Gunderson engraved a likeness of the young Elizabeth II for her first appearance on Canadian banknotes as the Queen, many people spotted a ‘devil’ in her hair! Angry letters were written to the Bank of Canada from Britain and the Commonwealth calling out the insult. The Bank relented and asked the engraver to re-do his art, thereby ‘exorcising’ the devil.

Money Talks exhibition gallery display of Queen Elizabeth II's portrait used in Canadian bank notes below, with the devil in the hair detail pointed out

A similar story about spotting a ‘bird’ in the ear of the current king’s coin portrait has been flying around, prompting vehement denials by Martin Jennings, the artist sculptor who created it!

One of the late Queen’s image – based on the plaster cast bust by Arnold Machin – has achieved iconic proportions as the world’s most reproduced artwork. Printed nearly 300 billion times on stamps, the bust is also a ‘monetary portrait’, appearing on banknotes of Bermuda in 2009.

The Queen was particularly fond of this bust and refused to change it as her age advanced, like her coin portraits did. It has an enduring, ‘forever young’ appeal.

A version of the ‘Dressed Head’ sculpture of Queen Elizabeth II, Arnold Machin, 1966, plaster relief © The Postal Museum

Bermuda's 5-dollar banknote showing a marlin and the Arnold Machin portrait of Queen Elizabeth II in bottom left corner

Money goddesses

The imagery on money can be deeply connected to social, political and cultural impacts money has on world societies. The very word ‘money’ is derived from ‘Moneta’, originally a title of the goddess Juno, in whose temple in Rome money was minted. She appears on a type of Roman coins from the Republican period, delightfully shown along with implements involved in money production.

Silver Roman coin depicting the goddess Juno Moneta, 74BCE © Ashmolean Museum

In Eastern cultures, deities associated with fertility and plenitude often double up as gods and goddesses for money, evidently because plenitude and prosperity are both connected to wealth, of which money is the most familiar form. ‘Mother’ goddesses thus also become ‘Money’ goddesses, many times identified by their attributes and associations.

By far the most popular is Shri Lakshmi from the Hindu pantheon. She is usually shown in association with lotuses - also a symbol of purity, re-juvenescence and fertility. Hariti, a ‘protector’ mother goddess from the Buddhist tradition is many times shown with a ‘horn of plenty’, whereas Panchika, her male consort, clutches a money-bag.

Lakshmi, Hindu goddess of wealth, early 20th century, chromolithograph on paper © Ashmolean Museum

Gold bullion bar 2023, showing Lakshmi the goddess of plenty © Royal Mint Museum

Relief sculpture depicting Buddhist deities Hariti and Panchika, with a purse, staff and cornucopia, 3rd to 4th century © Ashmolean Museum

Japanese New Year’s card showing money god Daikoku using an abacus and a woman with a rat running up her arm, after Keisai Eisen, 1828

Modern money and the face of popular culture

Modern money carries images often underpinned by its political setting. Colonialism introduced coins and banknotes to Africa, disrupting thriving and complex monetary cultures.

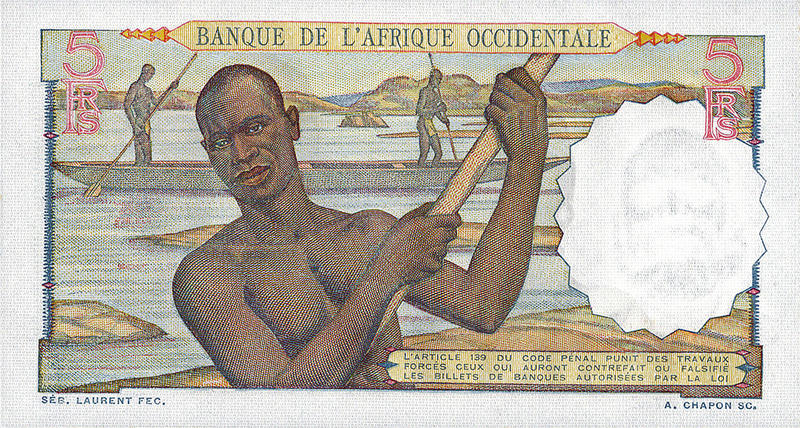

The imagery of colonial money in Africa is a fascinating and less-researched subject. Maurice Sebastien Laurent, a French banknote artist, shifted accepted conventions of money design by creating beautiful and vivid artworks depicting African people and landscapes.

But he also ‘objectified’ the colonised subjects by showing them as exotic, aloof, obedient and familial as if they were ‘enjoying’ the colonial experience!

5-franc note (face), Sébastien Laurent, 1942, Banque de l’Afrique Occidentale. Image courtesy of Paper Money Guaranty (PMG)

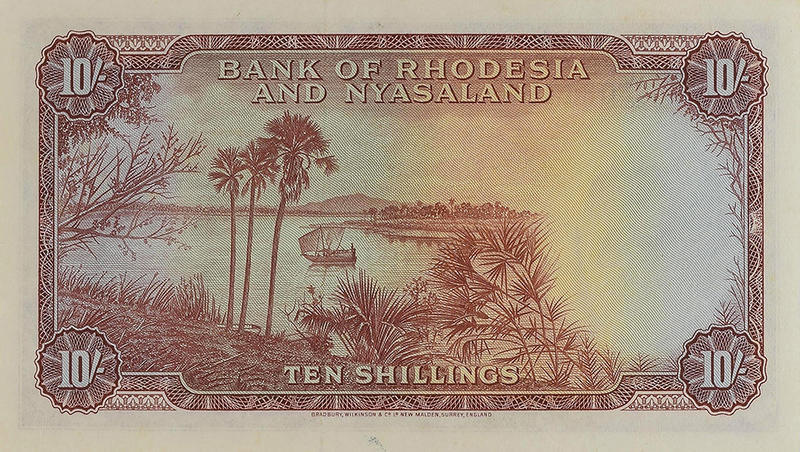

10-shilling note, 1956, Bank of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, reverse, view of Lake Nyasa

It is startling to note that the British colonial notes, on the other hand, ignore these populations altogether. The imagery on them is almost invariably landscapes – distant, wild and ‘long-shot’ views – suggesting a faraway fantasia, sometimes interspersed with animals.

Because money is familiar and functional, faces of banknotes and coins are often used as mediums by artists to make an artistic intervention.

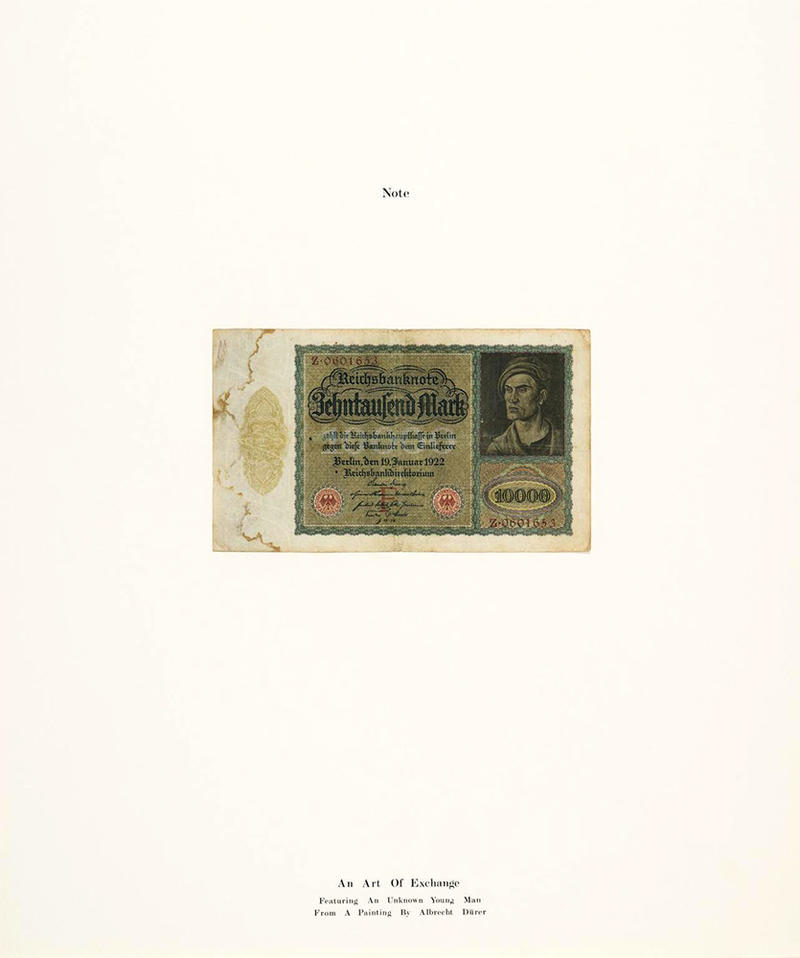

John Murphy highlighted the irony in the images of highly valuable and famous artworks by Dürer and Holbein the Younger appearing on German banknotes of post-WW-I period that were sometimes worthless within a matter of days and questioned the very basis of ‘value’.

An Art of Exchange Featuring an Unknown Young Man from a Painting by Albrecht Dürer, John Murphy, 1976 © Tate / John Murphy

Joseph Beuys, the German artist, scribbled his signature over circulating banknotes, defacing them and making them ‘artworks’ to ask the rhetorical question if human artistic potential can be equated to ‘Capital’.

Justine Smith’s clever collage of national currencies cut in shapes of nations to deliver an ‘explosive’ visual effect is an excellent comment on the 2008 financial crash. The faces of world leaders catch your eye in the scattered banknote pieces. Right at the heart of the artwork is a map of Russia, making us aware of the artist’s political standpoint.

The Bigger Bang–Black, Justine Smith, 2009, inkjet print © Haupt Collection

Artists respond to money in a variety of ways. They inspire money and its visuality; they also are inspired by money and its placement within human society.

These dynamics can be decoded by highlighting juxtapositions between the playfulness of Art and the power of Money. Much like famous artworks, money can present us with meanings and interpretations, layered within its visuality. We hardly appreciate such deep-seated aspects of something we carry everyday in our pockets.