EAST MEETS WEST IN THE VICTORIAN COLOUR REVOLUTION

5-minute read

By Madeline Hewitson

Research assistant for the Colour Revolution exhibition and Chromotope research project. The research presented in this article is part of the Chromotope project which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC).

Our current exhibition ‘Colour Revolution’ explores the colours of art, fashion and design in Victorian Britain. However, the 19th-century colour revolution extended far beyond the borders of the United Kingdom and spanned the globe.

From the splendours of the Indian sub-continent to the Japonisme craze among Decadent artists and authors, Maddie Hewitson reveals how colour forged connections and inspired art across the globe in the Victorian era.

Inside the East meets West gallery of the Colour Revolution exhibition. Photo Ellie Atkins © Ashmolean Museum

The golden age of travel

Spurred on by technological innovations such as the steamship and the telegraph, the Victorians were now connected at unprecedented speeds and exposed to previously unfamiliar art and material cultures.

Travel across Europe was well established by this period through trips such as the Grand Tour, so it was the empires and nations beyond Europe which held particular fascination amongst the Victorians.

They often referred to the Middle East, Asia and South-East Asia under the umbrella term ‘the Orient’ which was derived from the Latin word ‘oriens’ meaning East.

In the 19th century, the term the ‘Orient’ and the study of its cultures known as ‘orientalism’ had neutral connotations. However, these images were predicated on Western depictions of predominantly Islamic peoples and places.

Today, we understand that they were a biased European view of the ‘East’, and in many cases, pure fantasy and invention.

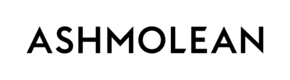

‘The gorgeous contributions of India’

At London's Great Exhibition of 1851, the Indian Courts, which were organised by the East India Company were the highlight of the entire show.

The design reformer Owen Jones described the displays as the ‘gorgeous contributions of India’.

India display in the Great Exhibition of 1851 by Joseph Nash, colour illustration showing the elephant sculpture © Royal Collection

Visitors revered India as one of the most important historical colour cultures as well as the crown jewel of the British Empire.

Above all, it was the Indian textiles – with their beautiful combinations of bright colours and stylised patterns – that caught visitors’ attention.

Luxurious Kashmir (cashmere) shawls, woven from the finest goat’s wool, arrived first in Europe as expensive gifts from Indian rulers. They became sought-after accessories for the European elite in the late 18th century and remained highly fashionable until the 1870s.

A British market to create imitation Kashmir shawls emerged in industrial textile centres such as Paisley and Norwich.

In 1846, the East India Company signed the Treaty of Amritsar with Raja Gulab Singh which established the state of Jammu and Kashmir, a region which produced these shawls.

As part of the treaty, Raja Gulab Singh agreed to acknowledge ‘the supremacy of the British government’ and to present it annually with ‘twelve perfect shawl goats of approved breed (six male and six female), and three pairs of Kashmir shawls’.

The Government passed these shawls on to Queen Victoria. However, as the queen she maintained a strict policy of only wearing British-made clothing in public, so she seems never to have worn them.

Kashmir Paisley shawl presented to Queen Victoria c. 1875, wool & silk © Joan Hart Collection

'It has dyed our spirits in colours that can never be washed out': artists in the Middle East

In 1869, Thomas Cook offered his first package holiday in Egypt: a 70-day, all-inclusive cruise down the Nile.

Many artists were at the forefront of this first wave of British mass tourism which centred on Egypt, Palestine and the territories which fell under the dominion of the Ottoman Empire.

Before the age of travel, artists were inspired by texts such as The Arabian Nights, a collection of medieval Persian folktales, which was first translated into European languages in the early 18th century.

Between 1800 and 1890, nearly a dozen illustrated editions of the text were published with illustrations of tales such as Aladdin, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, and Sinbad the Sailor by leading artists such as John Everett Millais and Gustave Doré. This beautiful painting depicts one of the main characters from The Arabian Nights, Scheherazade, who serves as the narrator for all the tales.

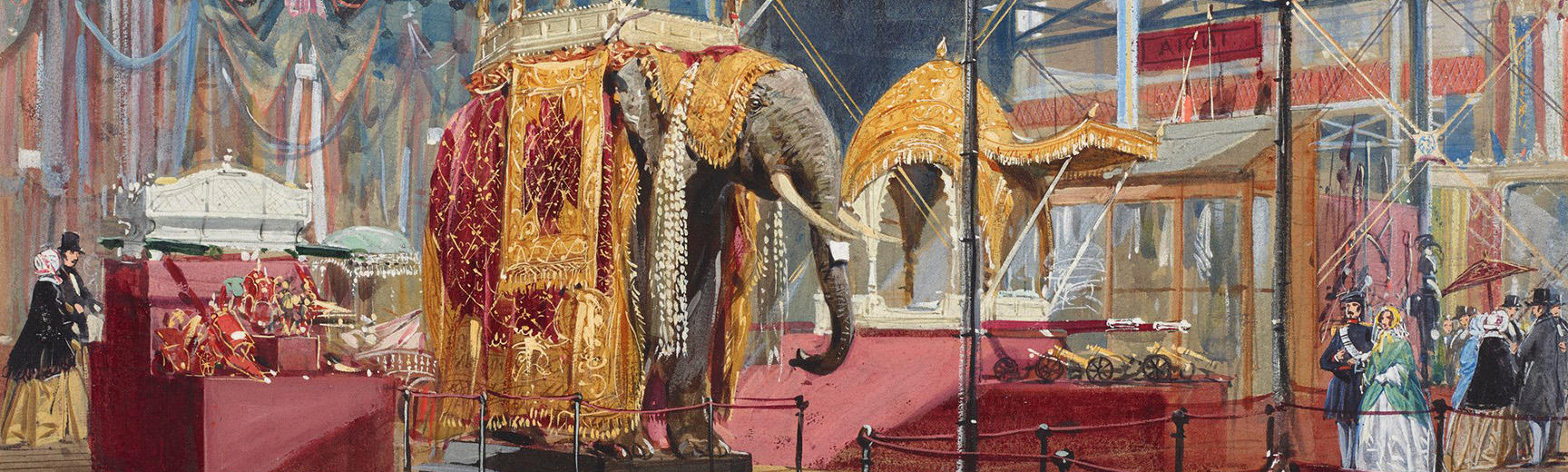

Scheherazade, Sophie Anderson, 1850-1900, oil on canvas © The New Art Gallery Walsall

These artists travelled to the Middle East in search of a transformative understanding of colour and light inspired by panoramic desert vistas, monuments with traces of pigments from the ancient world, and the vivid colour combinations found in Islamic architecture.

Landscape painting emerged as an important focal point for artists trying to translate the colours of their experiences into art.

As Edward Lear crossed into Baalbek in Lebanon in 1858, he annotated his pencil and watercolour sketches of the rugged landscape with written descriptions of his colour experiences.

Baalbeck from Lebanon, Edward Lear, 1858, watercolour & pen & black ink © Ashmolean Museum

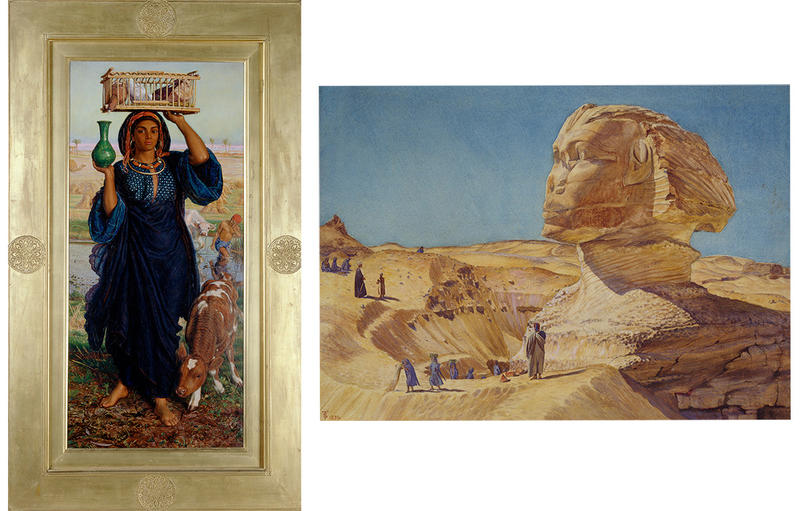

Lear first visited Egypt in 1854 with the Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt (who found repeated inspiration for his paintings on trips to the Middle East) and the landscape painter Thomas Seddon who tragically died in Cairo during a cholera outbreak.

Afterglow in Egypt, William Holman Hunt, 1861, oil on canvas and The Great Sphinx of the Pyramids of Giza, Thomas Seddon, 1854, drawing © Ashmolean Museum

Lear’s sketches were aide-memoires to prompt his memory back in the studio.

His other career as a nonsense poet influenced the spontaneous and witty quality of his annotations and he even referred to his art as ‘poetical-topographical’.

The Japonisme craze

Upon seeing the Japanese Court at the International Exhibition of 1862, the architect William Burges declared ‘if the visitor wishes to the see the Middle Ages, he must visit the Japanese Court’.

It was the first time Japanese art and material culture had been exhibited in Britain on a large scale. Before 1859, Japan had been a largely ‘closed’ society, resisting trade and tourism from the West.

The International Exhibition sparked a craze for all things Japanese and brought an unprecedented number of Japanese objects into Western collections which exercised a major influence on the development of fashion and design.

Alexis Falize jewellery, 1865-67 © Ashmolean Museum

Artists associated with Aestheticism began to collect Japanese art such as woodblock prints and kimonos.

James McNeill Whistler was at the forefront of the artistic craze for Japonisme. He was deeply inspired by the indigo hues used by artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige and incorporated them into his ‘nocturne’ paintings which explored the sensational effect of different colour harmonies.

High-ranking courtesan from the Shiebi House, Eisen Keisai, 1810-45 © Ashmolean Museum(right) Nocturne in Blue and Gold: St Mark’s Venice, James McNeill Whistler, 1880 © National Museum Wales

However, Burges’s comment suggested that Japan was a culture frozen in time when, in fact, it was undergoing its own rapid period of transformation.

An extraordinary board game produced using the new mass colour printing technologies was utilised as a highly effective tool for informal education and propaganda.

Japan Reforms Board Game, published by Yokoyama, 1887-1894, colour woodblock print © Ashmolean

The ‘Board Game of Japanese Reforms’ illustrates a range of sophisticated activities players could aspire to take part in as model citizens in the new Japan.

Activities include ballroom dancing, dressmaking with sewing machines, choral singing, participating in a sports day and attending festivals associated with the Imperial family.

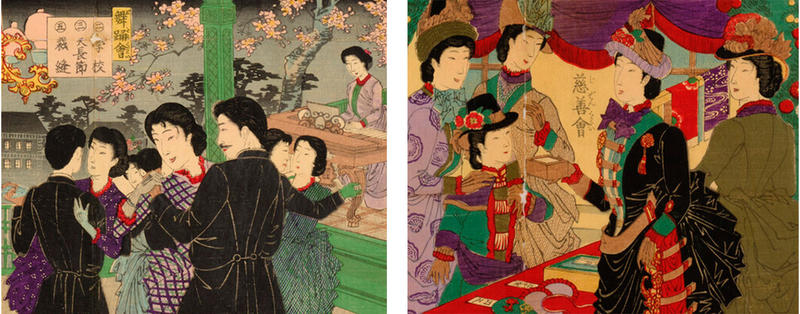

Detail scenes from the Japanese board game showing the influence of Western colours and styles in the depictions of the people portrayed © Ashmolean

The women are dressed in corseted aniline-dyed purple and green dresses and the men are in Western-style military uniforms, which the Meiji court formally adopted in the 1870s.

The board game shows how Japanese people responded to the colours of the European synthetic dye revolution and incorporated these new colours into their fashion and material culture.

Art's power to connect

Art is a powerful influence in an interconnected global world, which we can see today in the age of international auction houses and digital art. This was especially true during the 19th century – a period of exploration, imperial expansion and defining what it meant to travel and see the world.

Colour was no exception to this travelling impulse and moved across continents and borders in the art, fashion and design of many different cultures.

Some of the artworks discussed in this article are on show in our Colour Revolution: Victorian fashion, art & design exhibition. The exhibition opened on 21 September 2023 and runs until 18 February 2024.