THE REVOLUTION IN VICTORIAN FASHION

5-minute read

By Madeline Hewitson

Research assistant for the Colour Revolution exhibition & Chromotope research project. The research presented in this article is part of the Chromotope project which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC).

Push aside any dark and gloomy preconceptions you may have of the Victorians. Immerse yourselves in the explosive, colourful fashion of this eventful era - a time of enormous societal change and upheavals in science, nature and art.

Our misconception of Victorian fashion

We think of the 19th century through a monochrome lens. Popular films and television series have cemented images of Dickensian slums, factories belching with smoke and rivers running foul with pollution in the popular imagination to this day.

Perhaps the most enduring figure in this version of a ‘bleak’ 19th-century era is the woman after whom the period is named, Queen Victoria.

Portrait of Queen Victoria, 1900

Despite enjoying the latest fashion trends in her youth, after her beloved Prince Albert died in 1861, Queen Victoria assumed a uniform of black-and-white 'widow’s weeds' (the etiquette of mourning) until her own death in 1901.

Queen Victoria's mourning dress, black silk, c. 1898 © Historic Royal Palaces

These sober colours also dominated men’s fashion: tightly tailored suits and top hats with little opportunity for personal expression.

However, much of this monochrome imagery is a misconception.

During the Victorian period, fashion was just as popular and diverse as it is today. Inventions in the field of chemistry and discoveries made across the globe fuelled consumer trends for bright colourful clothing. The changing colours in clothing, particularly for women, were about to light up the fashion and art world, like never before.

Duchess Louise’s Queen Zenobia fancy dress, worn at the Diamond Jubilee Devonshire House Ball, 1897. Image © Historic Royal Palace / The Devonshire Collections

April Love by Arthur Hughes, 1855-6, oil on canvas © Tate Britain

Yellow moire and chiffon cape with yellow satin lining, silk c. 1898 © Fashion Museum Bath

From coal into colour, the aniline dyes

Historically, brightly-coloured clothing had been the preserve of the wealthy and powerful. In the ancient world, colours such as purple were associated with Roman emperors and the sails of Cleopatra’s barge. Mainly because it was incredibly expensive to extract the pigment from the only animal who produced such a colour, the murex snail.

Painted cast of the Augustus of Prima Porta © Ashmolean

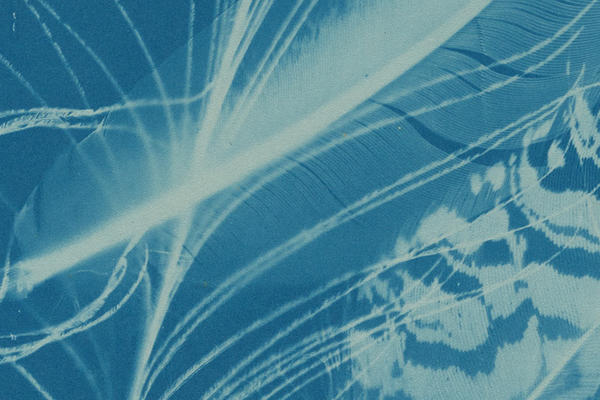

That all changed in 1856 when William Henry Perkin, an 18-year-old chemistry student, was conducting experiments alone in his rooms over the Easter holidays.

Perkin had been attempting to produce a synthetic version of quinine, the drug commonly used to treat malaria at the time. However, instead of a clear liquid, there was a reddish powder at the bottom of his beaker. When he then purified, dried and digested this unknown material with methylated spirits, it produced a dye. When applied to fabric it was a luminous purple.

Perkin had just invented the first synthetic dye, which he called ‘mauveine’.

Mauveine dye discovered by Sir William Perkin © Science Museum (Creative Commons)

While other scientists, including his teacher August Wilhelm von Hoffmann, a brilliant German chemist who was Head of the Royal College of Chemistry in London, had already been investigating the chemical composition of coal tar, Perkin’s genius lay in his idea to manufacture aniline on a massive scale and market it to the textile industry.

Before training to become a chemist, Perkin had originally wanted to be an artist and was obsessed with painting. So, perhaps it was this attitude towards colour as a material of expression that gave him the idea to paint the women of Victorian London is the most vivid colour science had yet to discover.

Colour for all, democratising Victorian fashion

Following mauveine’s introduction in 1858, purple became a wildly popular fashion trend. Women ordered dresses, parasols, handbags – even stockings and corsets in the colour du jour. In the privacy of the domestic sphere, men also took the opportunity to introduce colour to their wardrobes with ornate slippers and elegant smoking jackets.

Purple crinoline with ornate braiding © Manchester Art Gallery

Silk and wool pink, red, blue and purple stockings, 1862 © Fashion Museum Bath

Men's Berlin work slippers © Manchester Art Gallery

In 1859, Punch Magazine warned its readers that London was in the grip of a pandemic of ‘mauve’s measles’ that was ‘spreading to so serious an extent that it is high time to consider by what means [they] may be checked’.

An 1860s day dress worn by Mary Eleanor Cunliffe, daughter of a Baptist minister from Leicester, radiates in vivid purple intensity to this day.

Lady’s day dress, England, aniline-purple silk, about 1865–70 © Manchester Art Gallery

This is due to the fact that anilines were incredibly stable and not vulnerable to fading in light like natural vegetable dyes. Mary’s dress is just one example of how anilines brought colour to a much wider cross-section of Victorian society. Aniline dyes were cheap to produce and soon sold on an industrial scale.

Perkin’s discovery encouraged chemists across Britain, France, Germany and Switzerland to search for new synthetic colours from coal tar. In the following decades, dozens of new colours were synthesised – a new chemically-produced rainbow.

In 1861, an article entitled ‘The Triumph of Colour’ noted: ‘…never were the ladies of England dressed in such brilliant hues as the present day.’

By the dawn of the 20th century, however, it was Germany and not Britain that dominated the aniline industry.

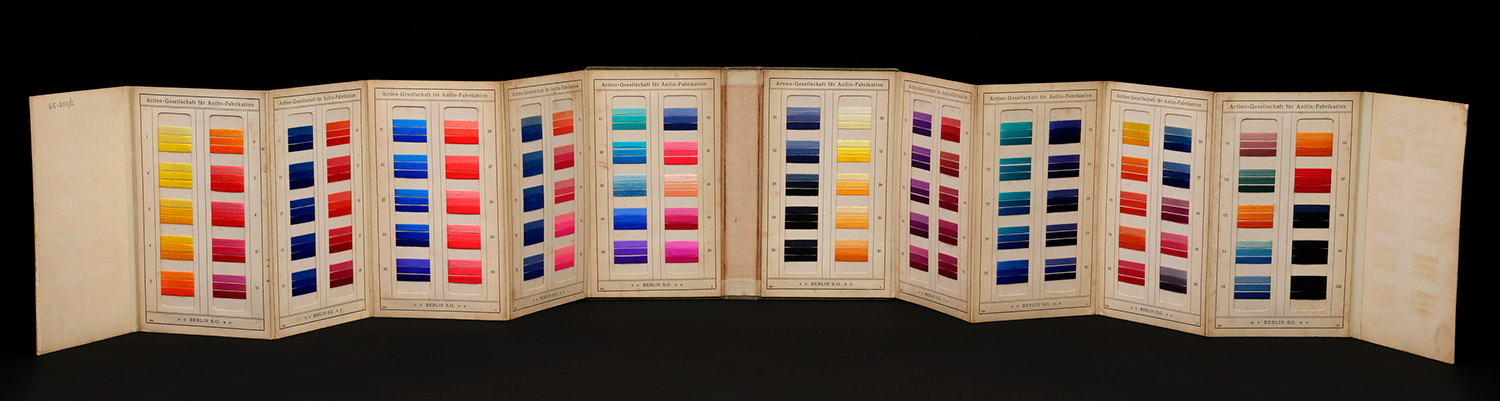

Synthetic dye samples, the Berlin Aniline Co, wool, card, c.1900 © History of Science Museum, University of Oxford

Their leading firms, businesses such as Bayer and IG Farben which you may recognise as pharmaceutical firms today, offered a huge variety of colours to textile producers all over the world.

Animals in fashion, murderous millinery

Colourful innovations in fashion weren’t just confined to chemistry labs. The Victorians were also inspired by the colours of the natural world. In the 1860s, Charles Darwin’s discoveries about the biological origins of humans and animals fascinated – and frightened – many people.

Designers took note of the way that the rich variety of colours across the animal kingdom could be incorporated into art and fashion.

Vivien by Frederick Sandys, 1863 © Manchester Art Gallery

However, sometimes this had grizzly implications. A horrifying quantity of animals and insects were killed to satisfy these new trends. Beetle’s wings and hummingbird bodies were particularly popular.

During one week at a London auction house in 1888, 400,000 hummingbird ‘skins’ came under the hammer. They were bought by the capital’s dressmakers and milliners to adorn fashionable hats, dresses and jewellery.

Victorian hummingbird necklace and hummingbird and beetle fan

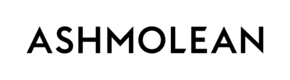

Both creatures, the hummingbird and the beetle, had a special quality that made them so appealing: their bodies shimmered and changed colours in the changing light. This effect, known as iridescence, is caused by the structural colour in their wings and bodies that refracts light.

For example, when Castalia Rosalind Campbell, the Countess Granville wore her tiara, necklace and earrings - all of which were decorated with South American weevil green-wing casings, they would transform from green to gold and back again, creating a dynamic piece of jewellery.

Lady Granville's beetle jewellery set made by the Phillips Brothers of London © British Museum

These statement pieces blurred the lines between scientific naturalism and fantasy.

Fashion influences on the early Suffragettes

The 19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche came up with a term to describe society’s obsession with beauty at the expense of everything else: ‘creative destruction that was creatively destructive.’ These fashion crazes which dangerously depleted animal populations captures the essence of this idea.

Victorian fashion took a particular toll on birds including the snowy egret, which went extinct in several North American regions for decades. After a generation of this ‘murderous millinery’, the consumers, mainly women, decided to step in and save the hummingbirds.

In 1891, two groups – the Plumage League founded by Emily Williamson and the Fur, Fin and Feather Folk founded by Eliza Phillips and Etta Lemon – merged to form The Society for the Protection of Birds (SPB). For many of the women who became involved in this organisation at the end of the 19th century, this was their first taste of political activism.

Several prominent members of the SPB went on to join Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union to advocate for women’s suffrage.

Emmiline Pankhurst, leader of the Votes for Women Movement, with her characteristic feather hat © National Archives

Suffragettes had popularly worn plumed hats until Lemon distributed a pamphlet amongst members which included the following warning: 'if women are so empty-headed and stupid that they cannot be made to understand the cruelty of which they are guilty in that matter, they certainly prove themselves to be unfit voters.'

The colour revolution continues today

From its origins in the 19th century, the colour revolution in fashion continues today with a kaleidoscope of clothing parading down the catwalk and the high street. Even famous Victorian colours are making a comeback.

The paint company, Pantone, recently named 'Viva Magenta' as its colour of 2023. Magenta was an aniline dye invented in France in 1859 and named after a famous battle the French won during the Second Italian War of Independence.

For the Victorians, fashion was a way to express popular and global trends as well as new discoveries in chemistry and biology. The conversations and debates these colours created can still be seen in the clothes we wear today.

Many of the objects and artworks discussed in this article are on show in our Colour Revolution: Victorian fashion, art & design exhibition. With thanks particularly to Manchester Art Gallery, Bath Fashion Museum and the British Museum for loaned objects. The exhibition opened on 21 September 2023 and runs until 18 February 2024.