HOW VICTORIAN WOMEN SHAPED COLOUR TECHNOLOGIES

5-minute read

By Madeline Hewitson

Research assistant for the Colour Revolution exhibition & Chromotope research project. The research presented in this article is part of the Chromotope project which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC).

In our major exhibition Colour Revolution: Victorian Art, Fashion & Design, we explore some of the gendered conceptions around colour, but also tell a new story about the role that many Victorian women played in shaping new colour technologies. Here we highlight three of these early Victorian pioneers, Anna Atkins, Sarah Acland and Loïe Fuller, who experimented particularly with cutting-edge photographic and light projection techniques.

The links between women and colour

There has been a long-standing association between colour and femininity in art. These associations were often linked to the prevailing notions of the period about gender. For example, during the Renaissance, feminine colore (colour) was seen as secondary to masculine disegno (design or drawing) and therefore, less important in an artist’s training or in assessments of their work.

In more recent times, fashion, interior design, and cosmetics, which centre on mixing, matching and combining colours, have all been perceived as feminine pursuits and largely marketed to women.

But the role that many Victorian women played in shaping new colour technologies was exciting and pioneering.

Inside the Colour Revolution exhibition. Photo Hannah Pye

Women seized the opportunity to reveal the world to audiences in ways they had never seen before: through the burgeoning technologies of colour photography and film.

Anna Atkins, 1799–1871, 'pretty plant' pioneer

Science, a discipline typically dominated by men, and photography were closely linked during this period. However, some sciences such as botany, the study of plants and flowers, were considered appropriate for women to pursue.

Similarly, as photography became more mainstream by the mid-19th century, it became a suitable ‘hobby’ for women to take up, often used to capture images of family and friends - like the work of Julia Margaret Cameron (below left).

My Favourite Picture of all My Works, Julia Margaret Cameron, 1867. WA.OA1352. © Ashmolean Museum

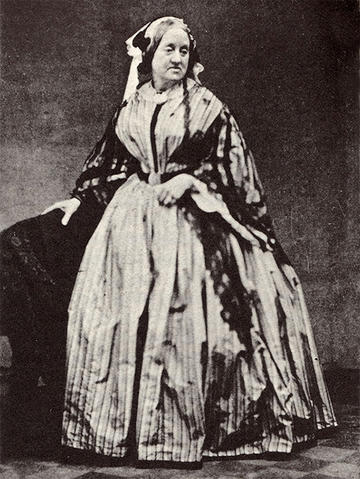

Portrait of Anna Atkins, c. 1861 (image in public domain)

However, for Anna Atkins, the daughter of a British Museum scientist and keen botanist, photography was a chance to experiment and bring together science and art.

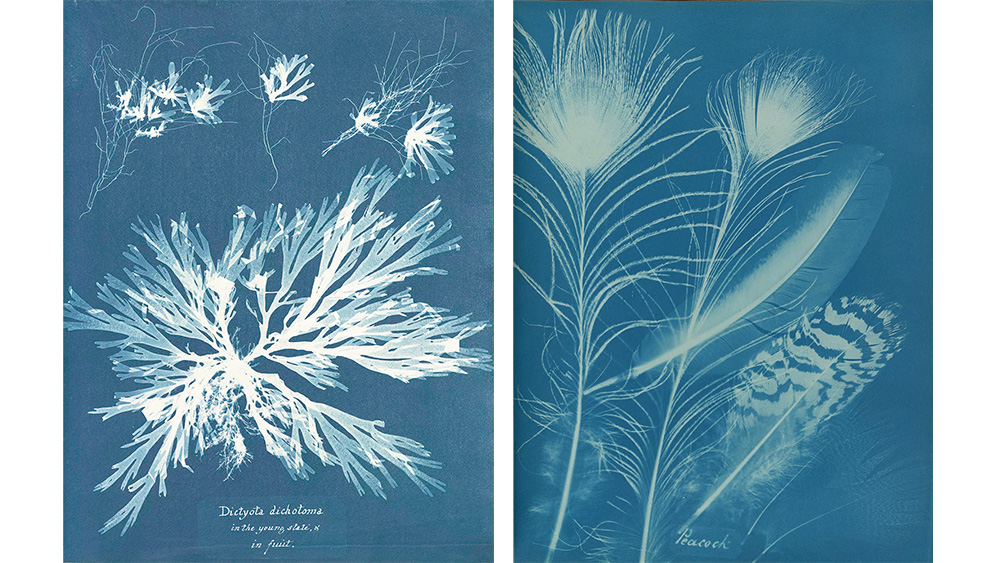

Atkins was at the forefront of one of the earliest photographic techniques – long before the quick snaps and ‘selfies’ of today. Instead, between 1843-54, she used John Herschel’s cyanotype process to create the world’s first photobooks of plants.

Cyanotypes are developed using light-sensitive, chemically treated paper. When exposed to light, the combination of ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide produces a vivid cyan-blue while anything placed on top of the paper to block the light remains a stark white.

Atkins chose to make photographs using marine plant life and, specifically, algae. Although this appeared to be a rather unassuming subject when she placed the plants onto the paper and exposed them to the sun, beautiful and ethereal images emerged.

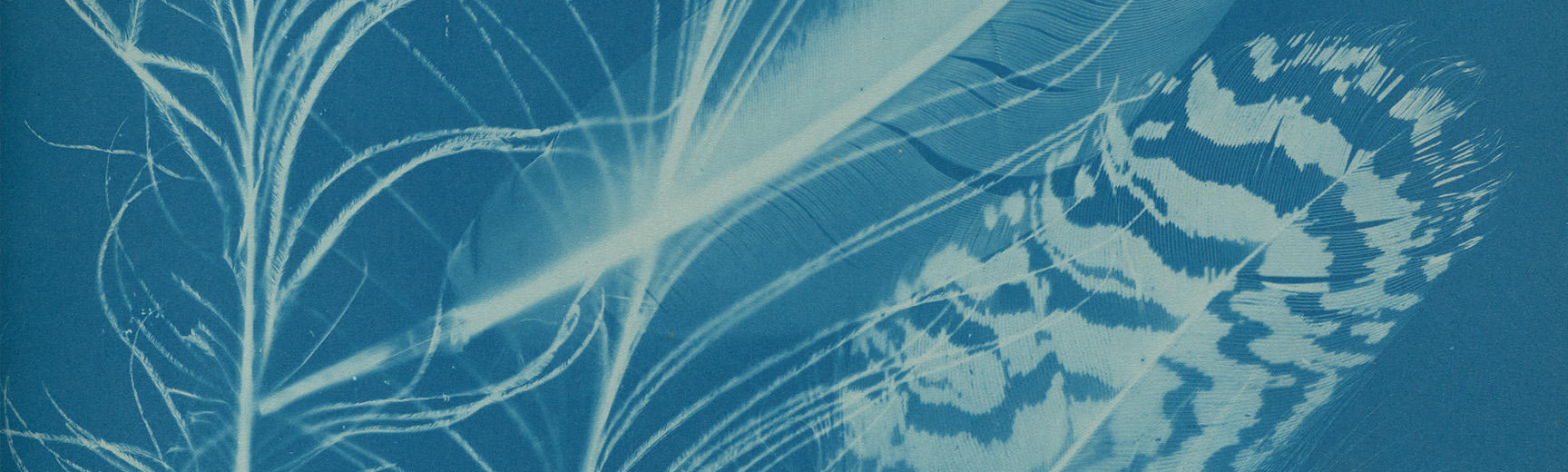

(l) Anna Atkins, Dictyota dichotoma, in the young state, and in fruit, 1848–49, from Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions Part XI. The Met Museum. (r) Peacock, Anna Atkins & Anne Dixon, 1861. Private collection, Courtesy Hans P. Kraus, Jr.

The photograms seem choreographed as the tendrils of algae samples and other flora and fauna dance delicately across the pages. Scientific drawings of plants had existed before, but Atkins used photography and cyanotype’s unique colour combination to make images that were co-mingled science and art.

Sarah Acland, 1849–1930, the world seen in colour

Although she wasn’t able to study for a degree at the University of Oxford, Sarah Acland benefited from being immersed in the university community where her father, Henry, was an influential professor as well as a good friend of the writer and art critic, John Ruskin.

The two men had worked together on the designs for the University Museum building (known today as the Natural History Museum) which fused the fascinating discoveries of Victorian scientists about the role of colour in the natural world along with Ruskin’s love of colourful Gothic architecture.

Design Studies for Capitals for the University Museum, Oxford, John Ruskin, c. 1855. WA1931.48 © Ashmolean Museum

In the 1860s, Ruskin agreed to become teenaged Sarah’s drawing tutor and in their lessons, imparted his beliefs on the power of colour to unlock the sacred beauty of nature.

In his manual Elements of Drawing he wrote ‘If ever any scientific person tells you that two colours are "discordant", make a note of the two colours, and put them together whenever you can.’

Sarah’s early work is full of Ruskinian ‘truth to nature’ naturalism, but she carried his lessons on colour forward as she forged a career in photography.

A Study of a Fish, Sarah Acland, 1877. WA.RS.UF.44.c © Ashmolean Museum

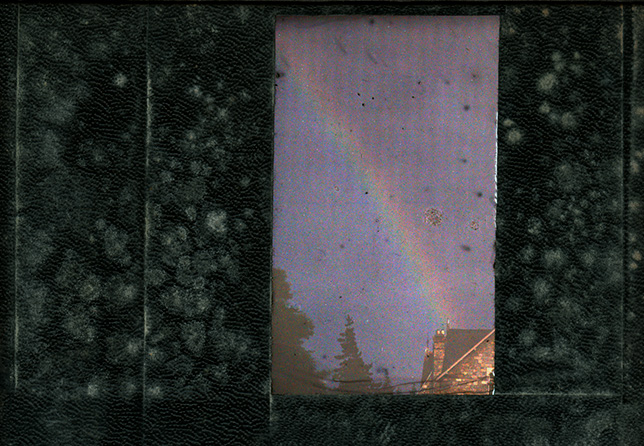

In 1894, Acland joined the new Oxford Camera Club as its first female member, later becoming vice-president. Her most important contribution to the field of photography was her work using the Sanger Shepherd method, which had been invented just before 1900.

The Sanger Shepherd process set a pathway for future colour photography, followed notably by Kodak’s dye-transfer process of the 1940s.

Instead of heeding Ruskin’s suggestion to combine two ‘discordant’ colours, this process involved taking three separate exposures on one plate – each through a different chromatic filter – before printing the red negative onto glass, and then green and blue negatives onto transparent celluloid that was then stained yellow and pink. These were combined onto one lantern slide which could either be shown through a projector or printed on paper.

Sarah Acland's Colour Photograph (Sanger Shepherd Lantern Slide) of a Peacock Feather by E. Sanger Shepherd & Co., London, 1899, used by Sarah Angelina Acland in 1900 © National Museums Scotland

Colour Photograph (Autochrome) of a Rainbow over Park Town, Oxford, Sarah Acland, c.1908 © History of Science Museum, Oxford

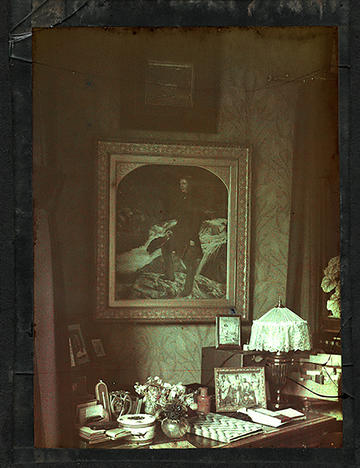

Acland paid tribute to her great teacher using another early colour photography technology, the autochrome. She owned Millais’s celebrated portrait of Ruskin and photographed it in her study at 40-41 Broad Street in the mid-1910s.

Using all of the colour technology at her disposal, she tried to capture the portrait’s colours as accurately as possible, in accordance with Ruskin’s truth to nature beliefs.

Sarah Acland, Colour Photograph (Autochrome) of the Millais Portrait of John Ruskin, hanging in Sarah Acland’s House at Park Town, Oxford, 1913–17 © History of Science Museum, Oxford

Autumn colours in New College, Oxford, Sarah Acland, 1907 © History of Science Museum, Oxford

Loïe Fuller, 1862–1928, the electric fairy

As photographs began to populate mass-produced magazines and albums in middle-class homes by the end of the 19th century, the next revolution in technology began: moving pictures.

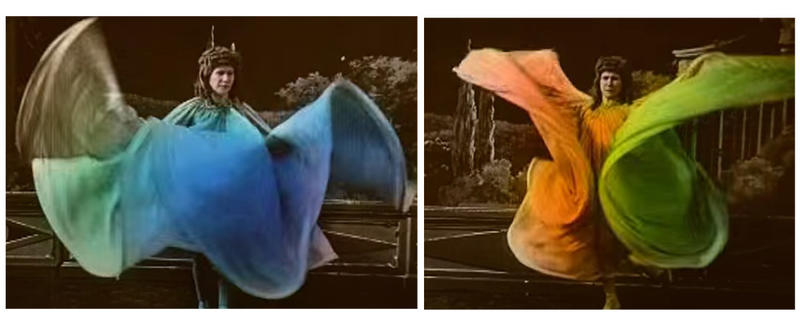

In 1892, the American dancer Loïe (born Mary Louise) Fuller debuted a new dance performance to rapt audiences at the Folie Bergère music hall in Paris. The ‘Serpentine Dance’ was a hypnotic choreography where Fuller manoeuvred ‘great waves of supple silk…creating innumerable orchids of light and fabric unfurling, rising, disappearing, turning floating’.

La Loïe Fuller. Poster advertising Loïe Fuller at the Folie Bergère, designed by Jules Chéret (1836–1933), printed by Imprimerie Chaix, Paris, 1893, colour lithograph. E.113-1921 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

However, the translucent white drapery Fuller wore was merely a backdrop for the kaleidoscope of colours which were projected on to it.

The marvel of the Serpentine Dance, which had 300 performances, was the patented electrical lighting system, invented by Fuller, which used rotating disks to project coloured lights onto the stage from many angles. Glass panels fitted directly into the stage floor provided dramatic up-lighting effects.

The dance became a spectacle where the jewel-like colours of the lights were constantly changing and merging and lit the swirling silk on an otherwise darkened stage.

Critics and admirers soon referred to Fuller as the ‘Electric Fairy’ and as the burgeoning French film industry grew in the early 20th century, they came to Fuller to capture her Serpentine Dance. Several films of Fuller, dating from around 1897 to 1902, including one by the Lumiere Brothers, show her performing the dance.

Stills from Loïe Fuller's 1905 film

The film was later stencil-coloured by hand with the Pathècolour process which used colours derived from the new synthetic aniline dyes. Until the advent of Technicolour in the mid-20th century, in film studios across Europe and America, nearly all of the hand-colouring of films was done by women.

The legacy of these Victorian pioneers

Beyond fashionable frocks and this season’s latest colour trend, Victorian women had a serious investment in new ways to share colour with the world.

They pioneered two of the period’s most exciting developments in colour technology and in the exhibition, we are proud to recognise several individual’s contributions to the Victorian colour revolution.

Many of the artworks discussed in this article are on show in our Colour Revolution: Victorian fashion, art & design exhibition. With thanks particularly to the V&A, National Museums of Scotland and the History of Science Museum, Oxford. The exhibition opened on 21 September 2023 and runs until 18 February 2024.

Watch Loie Fuller's original 1905 silent short film on YouTube